A black, round spot,— and that is all;

And such a speck our earth would be

If he who looks upon the stars

Through the red atmosphere of Mars

Could see our little creeping ball

Across the disk of crimson crawl

As I our sister planet see.

(from “The Flaneur,” in Boston Common, by Oliver Wendell Holmes)

Cold clear and blue the morning heaven

Expands its arch on high…

The moon has set but Venus shines

A silent silvery star

(from Selected Poems, Emily Brontë)

On June 5, virtually the entire globe should be able to witness an astronomical phenomenon, the Transit of Venus. This event, more rare than Halley’s comet, makes visible to observers the path of our “sister planet” Venus as she crosses the sun. The Transit occurs in 8-year pairs (the last was in 2004) once a century. This will be our last opportunity to witness the heavenly alignment until 2117.

The astrophysicist to note this pairing was the British visionary Jeremiah Horrocks (1619-1641). He followed Kepler’s correct prediction of the 1631 Transit with an accurate estimation of the 1639 phenomenon before his death at age 22. In discovering these facts about Horrocks, I was unprepared for the mad prophetic tone of his prose. I found the following on the “Transit of Venus” website.

But America! Venus! What riches dost thou squander on unworthy regions which attempt to repay such favours with gold, the paltry product of their mines. Let these barbarians keep their precious metals to themselves, the incentives to evil we are content to do without. These rude people would ask from us too much should they deprive us of those celestial riches, the use of which they are not able to comprehend.

I am indebted to my friend, Paul Zweifel for bringing the Transit of Venus to my attention. If enthusiastic as his forbear for this subject, Dr Zweifel’s prose is more cogent and carefully argued. And he has great pictures of the 2004 Transit on his website, from a trip to the Observatory outside Nice made for the celestial spectacle.

I was pleasantly surprised to encounter this starry summary from Thomas Paine.

The names that the ancients gave to those six worlds, and which are still called by the same names, are Mercury, Venus, this world that we call ours, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn… The planet Venus is that which is called the evening star, and sometimes the morning star, as she happens to set after or rise before the Sun…

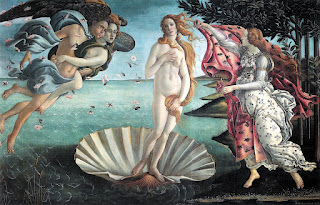

As Paine reminds us, the planets are named for ancient deities, and Venus (aka: Aphrodite) is the goddess of love. The stories vary as to her origin. According to the traditional sources (which informed Homer’s epics), Aphrodite was the child of Zeus and Dione. Hesiod assigns a more provocatively charged source for her incarnation. As most famously depicted in Botticelli’s “The Birth of Venus,” the goddess emerges “out of the foam of the sea.” This was no ordinary ocean spray, as it was formed from the “castrated manhood” of the god Uranus, which fell into the sea after his son Saturn (Kronos) “unmanned” him with a sickle. Saturn’s own son, Zeus (Jupiter) would depose him in the ten-year war that was the original “Clash of the Titans.”

(Botticelli: The Birth of Venus)

Aphrodite has inspired as many poems as Venus has been pictured in paintings and sculptures. One of the most famous of the “Homeric Hymns” is dedicated to her. Invoking the Muse – which we must assume to be Erato, the muse of love poetry – the hymn describes the power Aphrodite wields over the gods and humankind.

“Tell me, Muse, the deeds of golden Aphrodite… who stirs up sweet desire in the gods, and overcomes the tribes of mortal men, and the birds that fly in the air, and all the creatures that live on dry land and in the sea.” (from The Penguin Book of Classical Myths, by Jenny March).

Umberto Eco’s engaging compendium, History of Beauty lists a gallery of Venus representations. Eco’s anthology ranges from ancient sculptures like the Venus of Milo and the Asian goddess Lakshmi, through Renaissance portraits by Botticelli and Titian, to contemporary incarnations of the love goddess in the form of popular “sex symbols” like Marilyn Monroe. He underscores the dual associations of sacred and profane love by juxtaposing “nude Venus” with “clothed Venus.” The “Mona Lisa” may be the most famous of the latter incarnations, but Our Lady of Love exists in countless manifestations, from celebrated queens to venerated virgins.

(Velazquez: Venus with Mirror)

She has always been the Ideal, which has led to her idolization and her objectification. Though popular titles like “Men are from Mars, Women are from Venus” trivialize these distinctions, it is fitting that Earth revolves between Venus and Mars. Recall that the goddess of love was the most famous consort of Mars (Ares), the god of war. The “sea-born deity of love” was the mother of Harmony and Eros. Her famous daughter would wed Cadmus and found the great city of Thebes. While some sources cite Eros as a sibling or companion of the love goddess, Cupid’s arrows always bear the imprint of Aphrodite. Venus was the wife of the “lame smith” Vulcan (Hephaistos). Her trysts with Mars divided the gods in yet another potent symbol of mythology’s ever-present relevance for human affairs.

As we have seen from the Homeric Hymn, her powers of inspiration were frequently invoked. She was also implored to prevent heartbreak. Jenny March translates Sappho’s “Hymn to Aphrodite” thus: “Richly enthroned, Immortal Aphrodite, daughter of Zeus, weaver of wiles…. break not my spirit with heartache or grief.”

One of our great living classicists is the Canadian poet Anne Carson. Her book, Eros the Bittersweet, is an examination of the origins of that most enigmatic, ambivalent and human of concepts. Carson calls it an “erotic paradox,” this sweet and bitter proximity of hate and love. She cites Aphrodite’s address to Helen of Troy in the Iliad. “Don’t provoke me – I’ll get angry and let you drop! I’ll come to hate you as terribly as I love you.” In her wonderfully trenchant way, Carson writes, “Helen obeys at once. Love and hate in combination make an irresistible enemy.”

(The Pre-Raphaelite painter, Dante Gabriel Rossetti's "Helen of Troy")

The associations where Venus is concerned are dizzying. They are an example of Borgesian infinity, spinning out a seemingly endless web of examples in various guises as tales, poems, paintings, songs and stories.

Leaping back to another “erotic paradox,” the charged dyad of sacred and profane love, we connect to the mediaeval world of the troubadours. The Ideal object of love, as we have seen elsewhere in these musings, moved fluidly between venerations of the “Donna Angelicata,” the “Angelic Lady.” Dante’s Beatrice and Petrarch’s Laura are examples of human incarnations of these angelic visions. They are at once embodiments of sacred and secular love, and like Venus herself, a literal and figurative “heavenly body.” The crusading knight, Jaufré Rudel is identified with the lyrical trope of the “love from afar,” by idealizing a Princess from Tripoli he’d never met. His story is the subject of an evocative opera, “L’amour de loin,” from the Finnish composer Kaija Saariaho. Her monodrama, Emilie was created by our friend, Elizabeth Futral (who reprises her “most fulfilling and electrifying role” at this summer’s Lincoln Center Festival). Wagner’s German troubadour (Minnesinger) Tannhäuser is torn between sensual love for Venus herself, following an Odyssey-like seven-year tryst in Venusberg, and the saint-like Elizabeth, symbol of the sacred bond of human marriage.

Here is one of my favorite paintings about the subject that gives Dante Gabriel Rossetti his first name, called "Dante's Dream." A younger contemporary of Wagner, he was another "Renaissance man" whose love of the ancient world inspired modern works of symbolic potency. I hear Wagner's Venus-inspired music whenever I look at such sensually perfumed paintings.

In one of the ancient tales, Aphrodite is “the wise one of the sea” and was mother to Eleusis (which means “Advent”). Eleusis was also known as Ogygiades, reinforcing the Homeric parallel between the nymph Calypso (whose Island “paradise” was Ogyges, where Ulysses was stranded for seven years) and the goddess of love. The Eleusinian mysteries would reappear in the Christian celebration of Advent. As goddess of childbirth, Venus Genetrix is a pagan parallel to the Virgin Mary. Our inner life is richer for restoring these connections and not simply dismissing them as pejorative “myth.”

The “Song of Songs” contains some of the most sensual love poetry in the world, and scholars like Robert Graves have illuminated its associations with the goddess of love. Sappho describes a “sweet apple turning red,” and the Hebrew bard of the “Songs” says, “comfort me with apples for I am sick with love.” From the irresistible temptation in the Garden of Eden to the poisoned apple of fairy tales, the red fruit is a symbol bursting with meaning. Let’s consider one of its mythological appearances.

Recalling Carson’s quotation from the Iliad, we know the “face that launched a thousand ships,” Helen of Troy was under the sway of Aphrodite. In Michael Tippett’s Iliad-inspired opera, King Priam, the famous “judgment of Paris” is presented with ingenuity worthy of the masters of musical drama. Paris wins the hand of Helen when he awards Aphrodite the sacred apple as the winner of an Olympian beauty contest (which really “happened” on Mt Ida). As Tippett recreates it, Hera (Juno), the wife of Zeus, is represented by Andromache, Hector’s husband and Paris’s sister-in-law. Hera / Andromache represents “hearth and home.” Athena (Minerva) is played by Hecuba, Paris’s mother, symbol of wisdom and protection. Aphrodite is played by Helen, the incarnation of beauty and love. As reward for awarding the apple to Aphrodite, Paris wins Helen, and thus starts the Trojan War.

(Diane Kruger as Helen in the Wolfgang Petersen film, Troy)

Helen was the daughter of Leda, she of the swan, impregnated by the Aphrodite-inflamed Zeus whose disguise as a white bird fooled no one. Walter Pater describes Leonardo’s masterpiece, “Mona Lisa” (aka: “La Gioconda”) as “beauty wrought out from within upon the flesh.” In an image perfect for our celestial musings, he describes a Venus-inspired landscape as a “strange veil of sight” hovering in the “faint light of eclipse.” He compares “La Gioconda” to “Leda or Pamona, modesty or vanity… the seventh heaven of symbolical expression.” (from Studies in the History of the Renaissance.) In that single image we find our “sacred and profane” dialectic present on the planes of morality (“modesty or vanity”) and metaphysics (“the seventh heaven”).

The red apple is another “symbolical expression” of love and of spring. It is fitting this Transit of Venus occurs the night after the full “Strawberry Moon” of June, a symbol of the ripening year and the transit from spring to summer. The full moon of June 4 is the last lunar zenith before the summer solstice, and thus the Transit of Venus on June 5 heralds this “midsummer season” of love and plenty. In The White Goddess, Robert Graves says the “Rose of Sharon and the lily of the valleys” in the “Song of Songs” is a reference to the red anemones associated with the blood of Adonis, one of the mortal lovers of Venus. “Venus and Adonis” was one of Ovid’s famous “Metamorphoses,” and the subject of one of Shakespeare’s greatest poems.

(Titian: Venus and Adonis)

Aphrodite’s other famous couplings with mortals include those with Pygmalion, “the dwarf,” who loved a statue of the goddess so pitifully she animated the relic to life. Pygmalion is the name of the George Bernard Shaw play on which My Fair Lady is based. Her most important heaven-to-earth union was with the cowherd, Anchises, who became the father of Aeneas, the subject of Virgil’s unfinished epic, The Aeneid. Of the Venus of Melos, Pater paraphrases his friend Oscar Wilde’s couplet, “O for one midnight and as paramour / The Venus of the little Melian farm.” Might Wilde be describing the setting where Aeneas, the heroic champion of Italy, was conceived?

(Venus of Milo)

In The Death of Virgil, Hermann Broch leaves us satellites of lyrical wisdom in an epic novel of the great Roman's poet's last days. “Many things that are at first mere presentiments gain their inner meaning only by time.” Virgilian operas from Purcell’s compact Dido and Aeneas to Berlioz’s epic Les Troyens attest to the crescendo of “inner meaning” over time.

The “music of the spheres” is one symbol of the kinship of mathematics, astronomy and music that has been noted by poets for centuries. Of Virgil’s fertile imagination, Broch writes, “the singing of the spheres did not cease for him, he kept on hearing it, it continued to sing because he remained human.”

The author of Galileo’s Daughter, Dava Sobel observes, “the spheres of science and poetry probably intersect in all eleven dimensions.” In the November 2006 volume of Poetry magazine, her essay “The Earth Whirls Everywhere” references planetary poems by Robert Frost, Diane Ackerman and John Ciardi. In her book, The Planets, she “used poetry throughout the chapter about Venus as a way to equate the planet with beauty.” She notes the timelessness of poetic invocations of “the evening star” and “the planet of love.”

It is amusing to pull out Frost’s satirical quasi-Platonic dialogue poem, “The Literate Farmer and the Planet Venus” (with the self-deprecating subtitle, “A dated popular-science medley on a mysterious light recently observed in the western sky at evening”). The “Evening Star” itself inspires a rich associative list ranging from Edgar Allen Poe to John Clare (invoking Venus’s synonym, “Hesperus” or Vespers). William Blake and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow wrote evening star poems. Schubert’s friend, the classicist poet Johann Mayrfhofer inspired one of the composer’s greatest unsung songs, Abendstern. Louise Bogan may be most known to musicians for “To be sung on the water” (its title refers to a famous Schubert song, An den Wasser zu singen). "To be sung on the water" inspired Samuel Barber’s final – and most haunting – a cappella choral work. In another poem from the same collection, she describes the “Evening Star” as a “Brief planet, shining without burning.” Though she may not be referring to the Transit of Venus, in which the “brief planet” will appear as a small black dot in front of the fiery sun, her description evokes the phenomenon.

Venus has inspired other contemporary poetic riffs. In “Against Botticelli,” Robert Hass refers to the “sacking of Troy” and that which “survives imagination / in the longing brought perfectly to closing.” I don’t think he’s referring to Dido’s lament, but his Bosch & Goya associations are fascinating. In another Erato-inspired poem, Conrad Aitken translates the Birth of Venus into something wholly "other." “Sea Holly” is a mysterious nymph-like creature, “begotten by the mating of rock with rock” in “the fruitful sea.” Galway Kinnell, echoing the Romantics, opens “Last Gods” with a timeless image of sensual beauty. “She sits naked on a rock / a few yards out in the water.” The composer and bandmaster John Philip Sousa was inspired by the same 1882 Transit of Venus that prompted the Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr. poem in the epigram above.

Poets of all ages have tried to restore our connection to the “lost gods.” Gérard de Nerval followed the “Evening Star” like a magi guided by her heavenly course. He reenacted the journey of Virgil / Aeneas through darkness into light. In his fantastic dream world he communed with these seemingly remote deities and participated in the mysteries of Eleusis. He didn’t record a literal Transit of Venus, but noted the “heavenly vision” of the “Evening Star,” and felt as if he “ascended into its dizzying heights.” Our communion with celestial bodies engendered by events like the Transit of Venus is an opportunity to reconnect. There are many paths towards this worthy goal. We might attempt to reenact one of the ancient mysteries or rites or celebrate the coming solstice. We might honor the proximity of the Full Moon and the Transit of Venus with a midsummer festival or recreate a festive bacchanalia. Or we might simply watch the celestial phenomenon (which begins at approximately 6 pm EST) and marvel at another wonder of the universe.

Thomas Paine died in 1809, the year before Nerval was born. His amazement at our capacity for inquiry, experiment and discovery is as inspiring as it is timeless.

It should be asked, how can man know these things? I have one plain answer to give, which is, that man knows how to calculate an eclipse, and also how to calculate to a minute of time when the planet Venus in making her revolutions around the sun will come in a straight line between our earth and the sun, and will appear to us about the size of a large pea passing across the face of the sun. This happens but twice in about a hundred years… and has happened twice in our time, both of which were foreknown by calculation. It can also be known when they will happen again for a thousand years to come… As, therefore, man could not be able to do these things if he did not understand the manner in which the revolutions of the several planets or worlds are performed, the fact of calculating an eclipse, or a transit of Venus…

(from The Plan and Order of the Universe)

(from the 2004 Transit of Venus)

2 comments:

Scott, this is in incredible essay!

I want to reread it several times to fully understand it. As an opera intendant, however, you might have pointed out that there is actually an opera entitled "The transit of Venus" by Victor Davies. See

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Transit_of_Venus_%28opera%29

Also in Act IV of "Le Nozze di Figaro" Figaro refers to the little imbroglio between Vulcan, mars and Venus, if I recall correctly.

Paul

Thanks, Paul! I hadn't heard of the Davies opera. I tried to cover my bases by referencing the "infinity" of associations, but I knew you'd come up with some! I also neglected to mention Henze's "Venus & Adonis" and Holst's "The Planets." Venus also appears in Ligeti's absurdist opera, "La Grand Macabre" (which has an astronomer named Astradamors, for inquiring minds).

Cheers,

Scott

Post a Comment